Celebrating 100 years of Edward Gorey

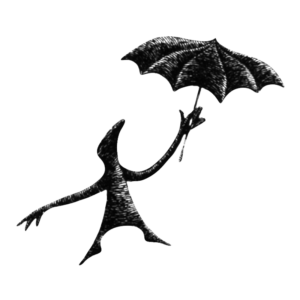

Edward Gorey’s extraordinary imagination continues to captivate and inspire audiences worldwide. Renowned for his intricate pen-and-ink drawings, clever storytelling, and a distinctive blend of gothic elegance and playful whimsy, he left an indelible mark on the worlds of art, literature, and design. His work transports us into a universe that is seemingly familiar, yet slightly askew—where mysterious partygoers don lavish fur coats and Victorian frocks, delightfully mischievous creatures become house guests, cats and ballerinas abound, and tragedy regularly strikes in humorously unexpected ways.

Beyond Gorey’s artistic legacy, his philanthropy and commitment to advancing the welfare of all living creatures, big and small, continues to live on through the work of the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

We invite you to join us in commemorating Gorey’s centennial year—a full 365-day celebration!

Sign up for our mailing list to stay up to date on special events, exclusive product releases, and more.

Centennial Tributes: A Call for Curious Creations!

Edward Gorey’s world of eerie wonder has delighted and unsettled us for generations. And now, we invite you to be a part of it!

Help us create a robust global tribute filled with artistic homages to Gorey’s singular imagination. Top submissions—whether in ink, verse, or the unexpected—will be enshrined in a commemorative digital gallery and featured at an exclusive 2026 event. Exceptional standouts will also receive a peculiar delight from the Trust’s archive.

More information and submission details, coming soon.

A Birthday Gift for Edward

In honor of Edward Gorey’s 100th birthday, a gift to The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust ensures that his creative legacy lives on by preserving his original art and writings for future generations to discover and cherish. Your donation also helps continue his unwavering dedication to animal welfare and the protection of all living creatures. The Trust is a 501(c)(3) organization, and all contributions are tax-deductible.

Mark Your Calendar!

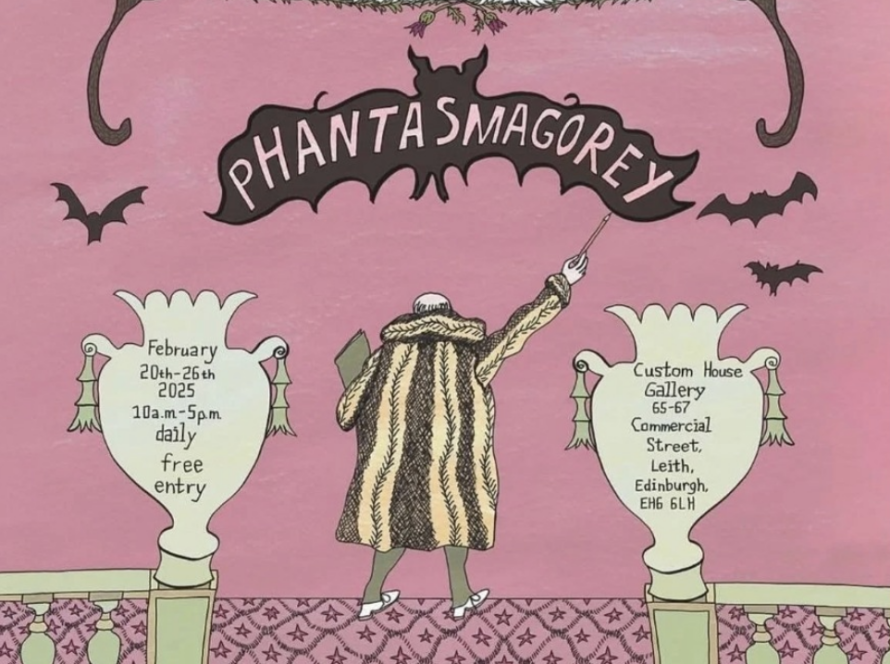

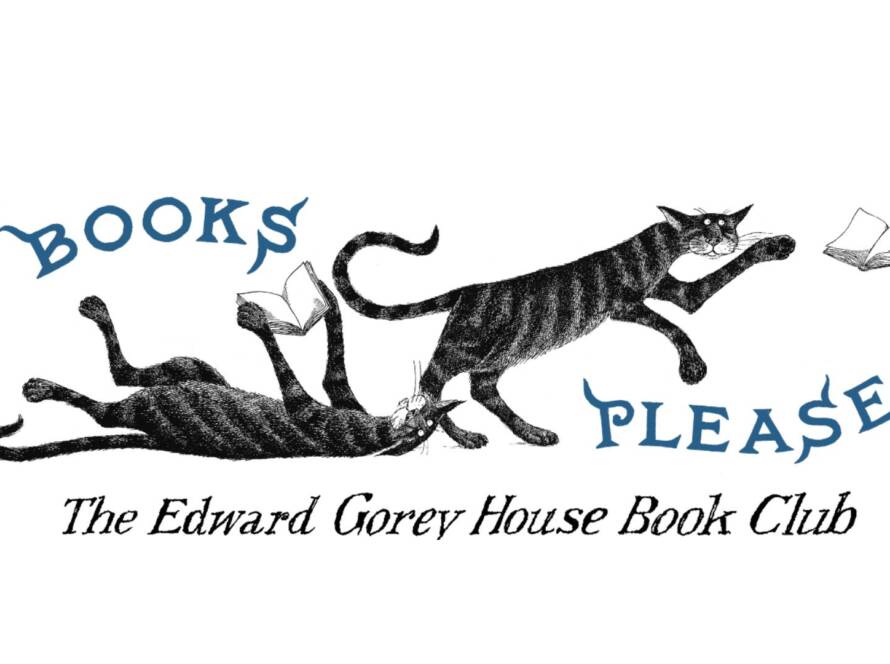

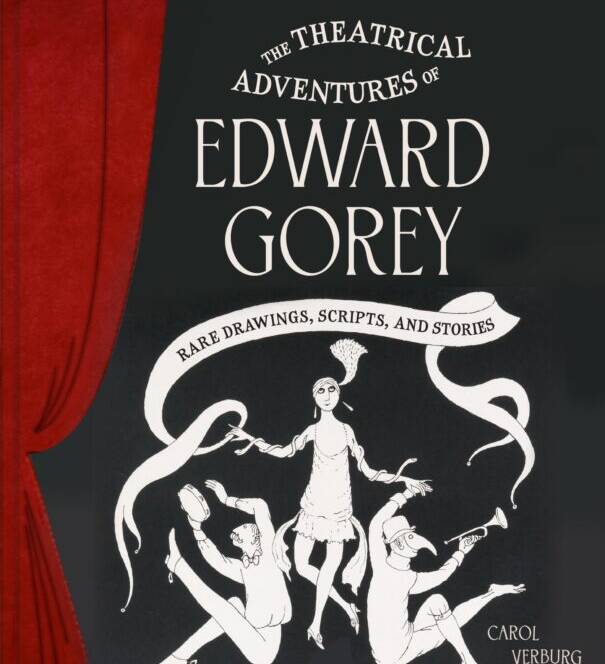

Search our calendar for details on all things Gorey happening around the world in honor of his centennial year. Discover new exhibitions, special events, literary gatherings, exclusive product launches, new book releases, and more!

If you are organizing an event and would like us to consider featuring it on our website, contact us at [email protected].

⏳ Coming soon

⏳ Coming soon