By Gregory Hischak

“Just do the steps”

George Balanchine (Mr. B’s instruction to dancers)

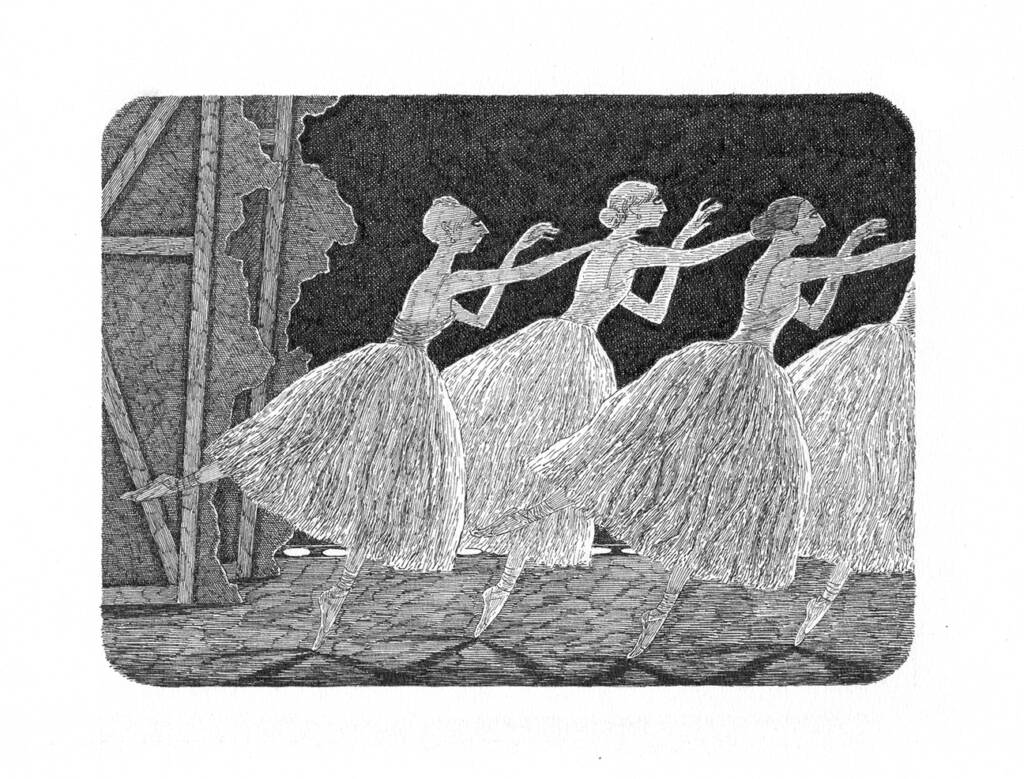

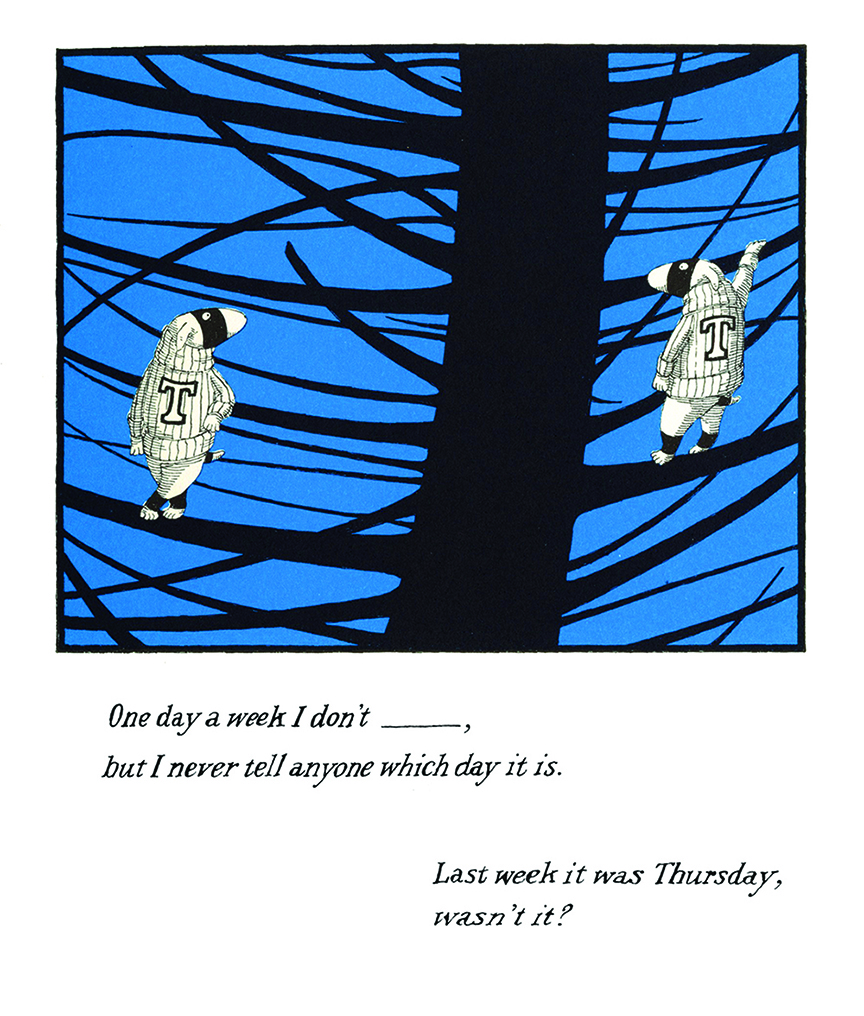

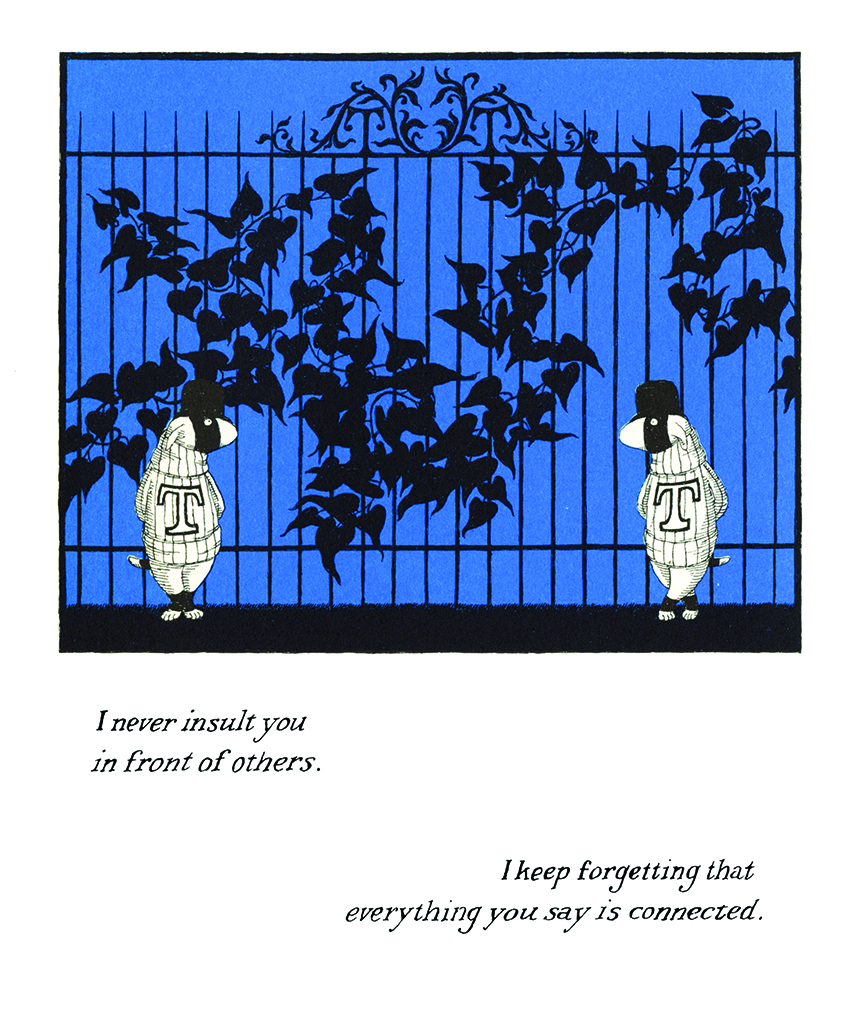

The Gilded Bat (1965)

Edward Gorey’s infatuation with the New York City Ballet, spanning some thirty seasons, from 1953 to 1983, is widely known. While he had his favorite dancers, his fixation remained centered on the choreography of George Balanchine. “Just do the steps” is famously Balanchine’s most repeated instruction to his dancers. Gorey, in his 1993 Ballet Review tribute to the dancer Diana Adams writes, “Properly considered, [‘Just do the steps’] somehow explains everything, and can be applied to whatever you can think of in both art and life.”

It was that quote that made the Edward Gorey House assemble our 2022 exhibit around Gorey and the New York City Ballet. We did so without much knowledge of Dance. We read about Balanchine, we read a lot of Arlene Croce (and filched much from her), and we built a narrative around some quasi-research and reckless speculation—which is how the House operates best.

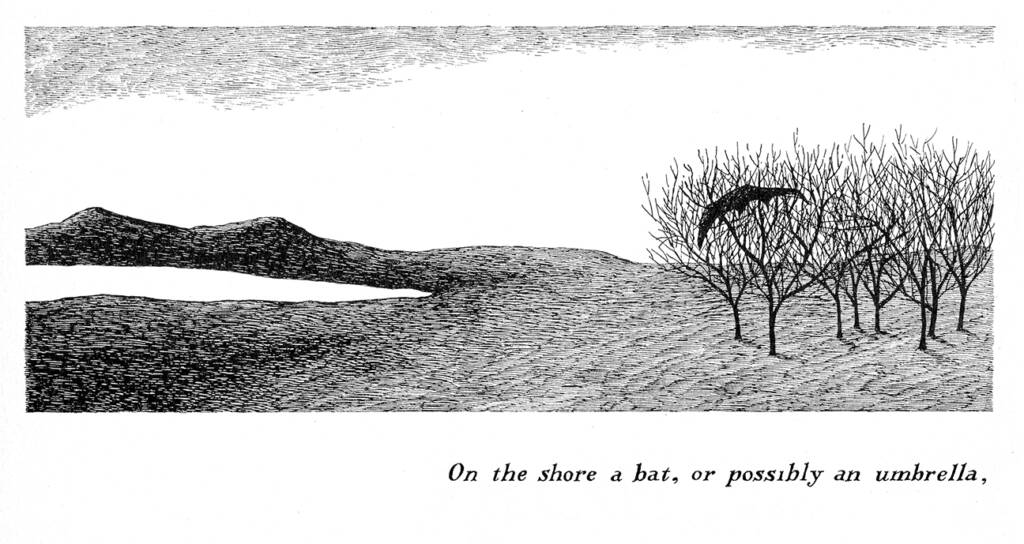

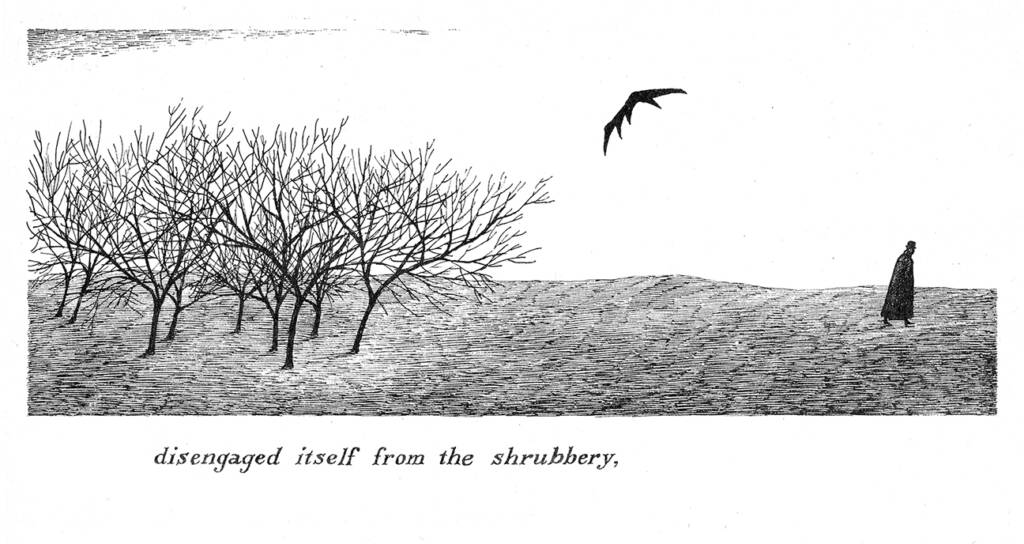

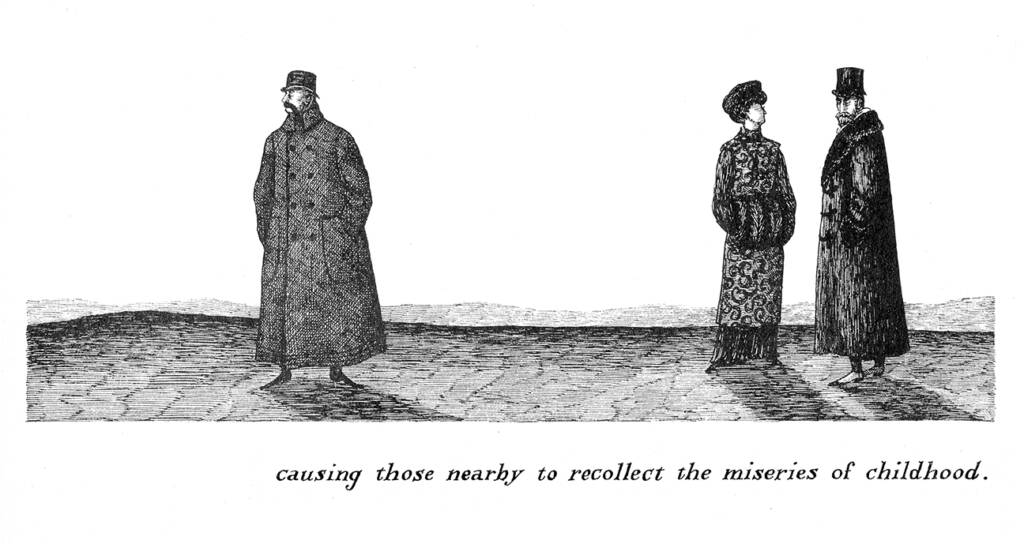

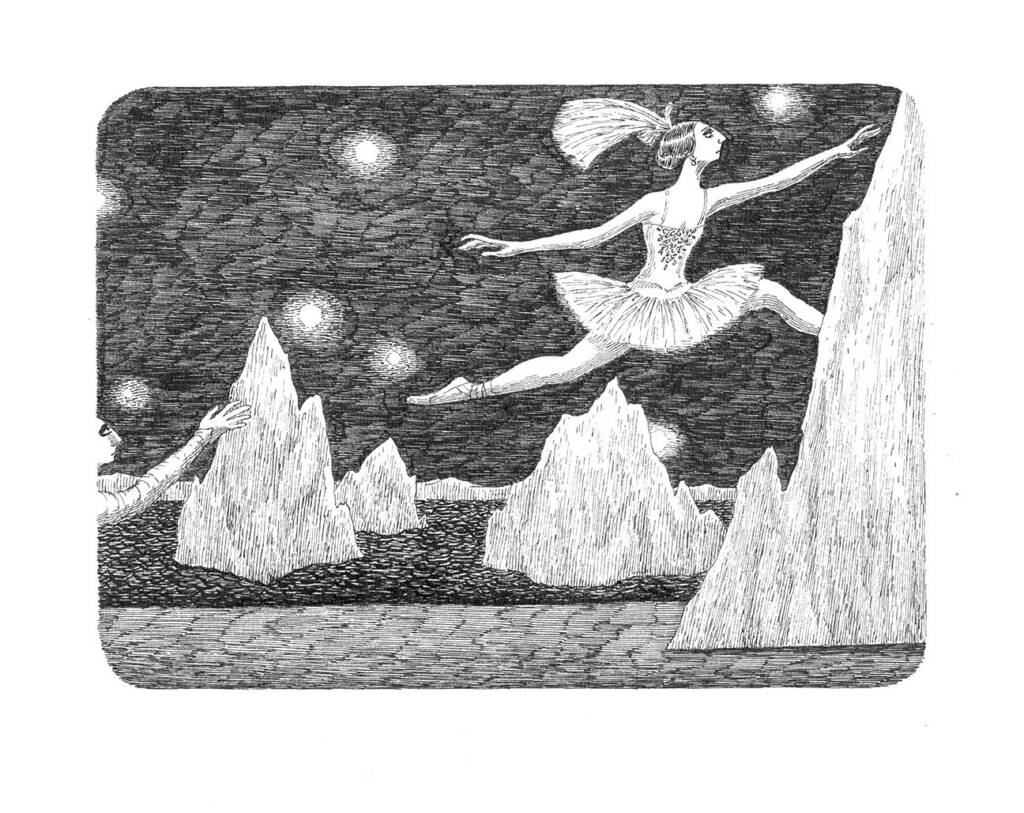

Doing the Steps offers the conceit that all 116+ of Edward’s self-authored books should be viewed as meditations on movement, pacing, cadence, tension, and release. In other words, all of Edward’s primary works are dance works—every single one. Oddly, his two books that are explicitly about dance, The Gilded Bat and The Lavender Leotard, are probably his least danceable books (though The Gilded Bat was staged as a ballet by Peter Anastos in 1989). The House contains enough gallery space to examine about nine of Gorey’s works as especially rich examples of movement including The Deranged Cousins, The Disrespectful Summons, L’Heure Bleue, and The Epiplectic Bicycle, among others, but it is the 1958 The Object Lesson which stands out, as its title suggests, as an object lesson is how choreography translates to ink and paper. Across the horizontal format of this beautiful book pacing and rhythm are established by the turn of a page and the turn of phrasing; its clever use of positive and negative space fills its long stage in startling ways; its Balanchine-infused storyless narrative makes The Object Lesson a work of expressive Nonsense—and infinitely danceable.

Another aspect of Doing the Steps was to explore this peculiar relationship between two artists: Gorey (who cited George Balanchine as his greatest inspiration and muse), and Balanchine (who if he regarded Gorey at all it was likely as the guy who showed up to read in the lobby of Lincoln Center almost every night). This was not a collaborative relationship—Balanchine staged ballets and Gorey attended them. In fact, the enduring mystery of Doing the Steps is why didn’t Balanchine and Gorey have any kind of relationship, or a heated rivalry, a collaboration, or even a casual discourse? That they remained almost perfect strangers to each other over thirty or so seasons seems unfathomable. Didn’t they encounter each other nightly? At the Carnegie tavern after the performances? In the NYCB studio where photographic evidence shows that Gorey was invited at least once to a rehearsal?

In fact, Gorey produced a decent amount of work for the NYCB: the 25th anniversary Lavender Leotard book, the Faux Pas postcards, the five positions poster (the NYCB’s de facto logo), buttons, subscriber materials—all probably negotiated through Lincoln Kirsten. That Edward would choose to skip the Tony award ceremony where Dracula was nominated for three awards to instead attend another NYCB performance speaks volumes about a man’s devotion to a dance company—and yet no collaborations with Balanchine ever materialize, or as far as we know, are ever considered.

Gorey is still contemporary enough to allow first-person narratives to color aspects of his life, and a lot of oral history walked into the House during our 2022 season. Oral history can be as insightful as it is contradictory. We can’t vouch for anyone’s accuracy of memory, we can only assemble it into a mosaic of occasionally battling pieces. For instance, visitors claiming that Balanchine watched every performance from the second-level balcony at Lincoln Center—the same section Gorey sat in—were countered by others swearing that Balanchine only watched from off stage. In oral history you take each account into consideration and then you build intriguing scenarios—like imagining that Balanchine and Gorey were within speaking distance of each other every night, or that maybe they never were within speaking distance, nor wanted to be. The foibles of human memory make for a prism, a fractured one, that allow you to view the same event through various perspectives, hazy or otherwise. That is the stuff stories are made of—and Gorey would likely disapprove of any history of him that was without wild contradiction.

For instance, Gorey’s attendance at the NYCB—did he actually attend every performance of the NYCB for thirty years? No, it only seemed like he did. His friend Robert Greskovic maintains that Edward averaged 160 shows a year (not including all the Nutcrackers). Others who showed up at the House swore he was there every time they were (though they couldn’t remember how many times that was), others claim that they never saw him. Some suggested that Edward got free admittance to most of the 1950s performances because his friends Mel and Alex Schierman both worked at City Center (Mel as Stage Manager for the Center, and Alex in the NYCB office). This would explain why in our inventory of ticket stubs here at the House (which we cataloged by year in preparing the exhibit) we have very few from the 1950s and early 60s. However, this wonderful theory is shot down by Alex herself who says they never gave Edward tickets. The tickets at the House number just under 5000. They indeed indicate about 160 shows were averaged in the 1960s seasons; the 1970s averaged between 200 and 225 performances; Gorey’s attendances in the 1980s reflect Balanchine’s deteriorating health and dwindling output. Were some tickets thrown out? Would Edward throw them out? Absolutely not. Were they thrown out after his death, or did they even exist in the first place—does it really matter? Isn’t 5000 performances impressive enough?

Those 5000(+) performances viewed regularly from the early 50s to the early 80s—modern ballet masterworks that evolved with every performance and over numerous seasons—were a vast creative reservoir for Edward. That it was maybe 8000 performances doesn’t change the story much: Gorey was fixated by Balanchine’s process and possibly appropriated it—or more likely, he just recognized the process as so much akin to his own.

“Just do the steps,” as Gorey wrote, can be applied to almost anything in the art of life and thus ends up meaning many things. It could refer to how you build a piece of art up from its foundation (be it basic dance steps, underpainting, a pen stroke, or chord progression). The foundation needs to be there so that if things collapse then they collapse properly. As a draftsman, Gorey builds interlocking, interconnected lines—all conforming to a solid premise. As a storyteller, he utilizes familiar tropes: the orphan, the innocent, the cad, the suspect, the goddess-maiden-vamp, the red herring—all recognizable archetypes and devices that allow you to settle in. As an artist, Gorey quickly leads you astray and throws questions at you without answers. Because of that solid foundation he’s built you follow—and that is what it means when they say you’ve stepped into the artist’s world.

While there are scholars who could spend enormous effort pairing Gorey’s works with Balanchine’s, the House doesn’t have the attention span for such opuses. It is an interesting narrative to say that Gorey attended every performance of the NYCB and sat within feet of Balanchine. Likewise, the narrative of a man who just sees a lot of NYCB and only occasionally spies the creator of the works doesn’t change the fact that Gorey was, in his words, trying to emulate Balanchine’s thinking.

What the House does each year is speculate on what moves an artist (and) say “what if we look at these works again—only this way now.” Gorey allows us an infinite number of interpretations and he establishes no boundaries where any interpretations outside of which are wrong. Gorey always leaves the reader as the final interpreter of his work—he has merely laid out the steps.

Gregory Hischak