By Malcolm Whyte

The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust has partnered with writer (Gorey Secrets, Great Comic Cats) and Gorey collector Malcolm Whyte to publish articles and chapters from his most recent work, Edward Gorey Tales Explored, on our Gorey Voices blog. Over the next few months, the Trust will showcase approximately 15 articles written by Mr. Whyte, each focusing on a different book by Edward Gorey. This collaboration offers a wonderful opportunity to delve deeper into Gorey’s works through the perspective of one of his most avid followers.

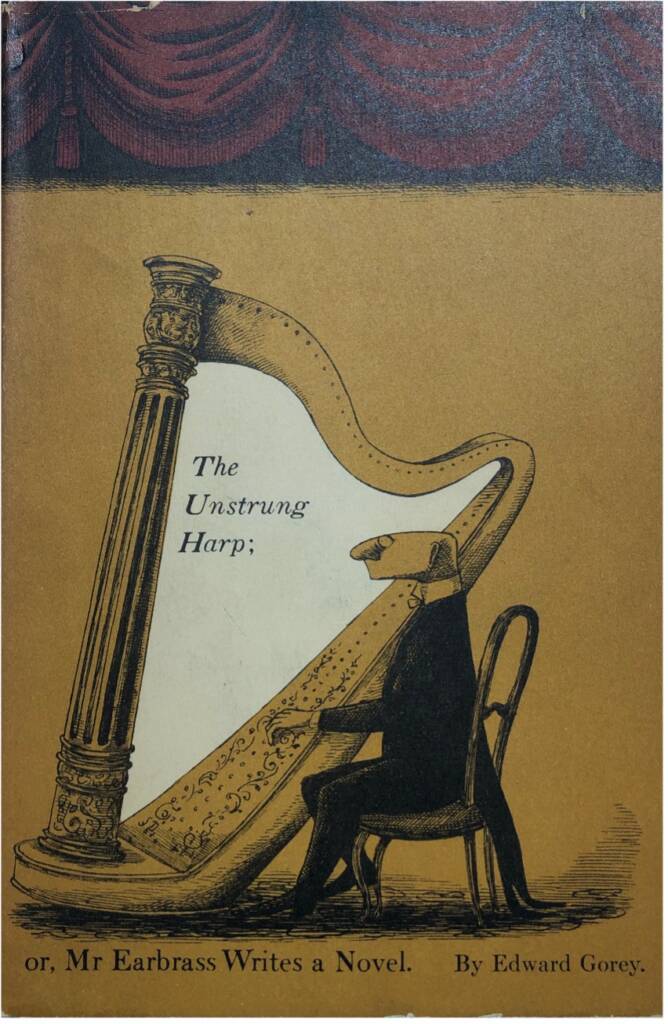

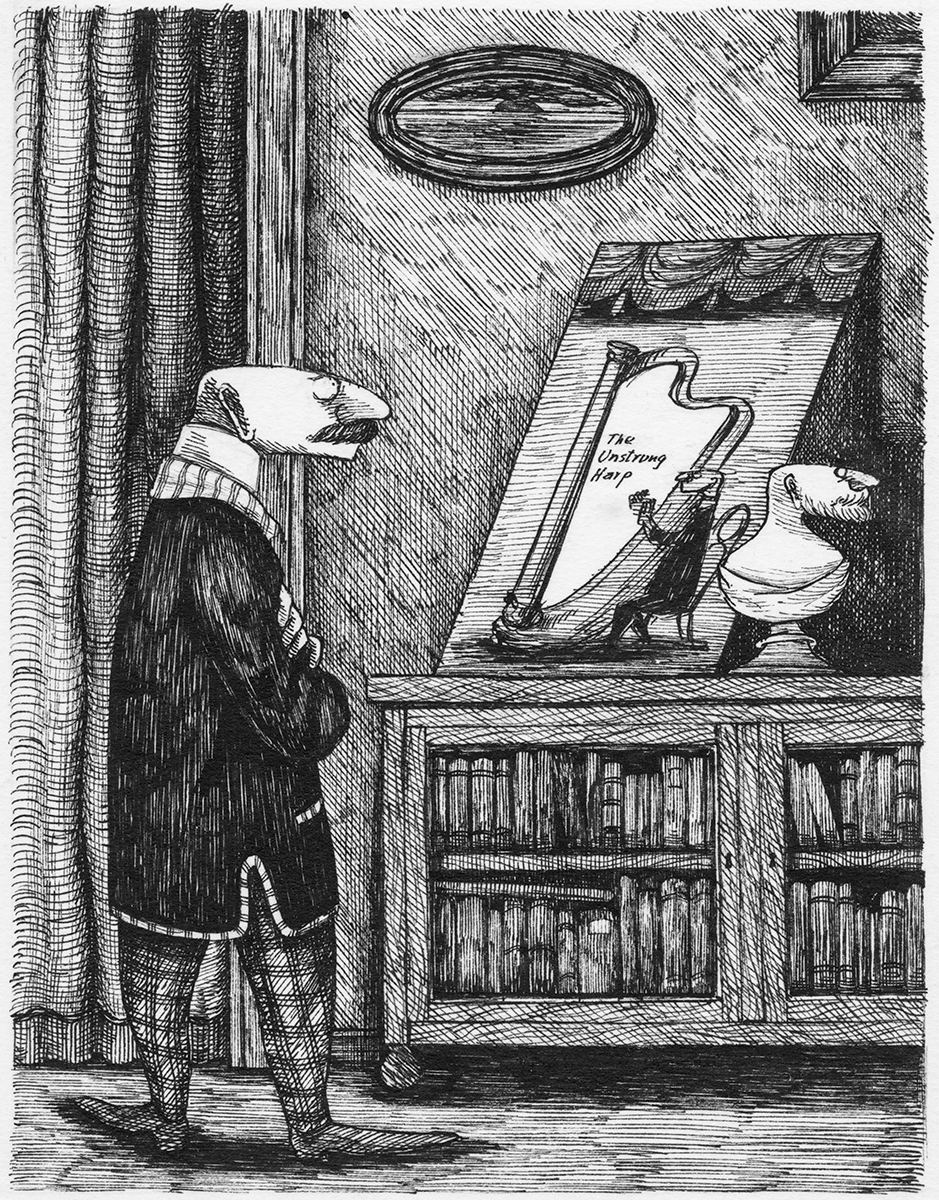

Gorey’s first published book is a knowledgeable, grinful study of the life of a professional author. Small in size (7½ x 5¼ inches), the 32 pages of text (the most text in any of his books) present a concise, but thorough accounting of the writer’s agonies of confronting the blank page, corralling elusive adjectives, slogging through endless revisions, and, after all is done, suffering cocktail party critics. The martyr in these literary tribulations, and protagonist of The Unstrung Harp is Mr. C(lavius) F(rederick) Earbrass, well-known author of the novels A Moral Dustbin, More Chains Than Clank and The Hipdeep trilogy, which he wrote at his stately nineteenth century home, Hobbies Odd, near “Collapse Pudding in Mortshire.” Despite the struggle, Mr. Earbrass soldiers on. “On November 18th of alternate years [he] begins writing ‘his new novel’ with a title he chose at random from a list of them he keeps in a little green note-book.”

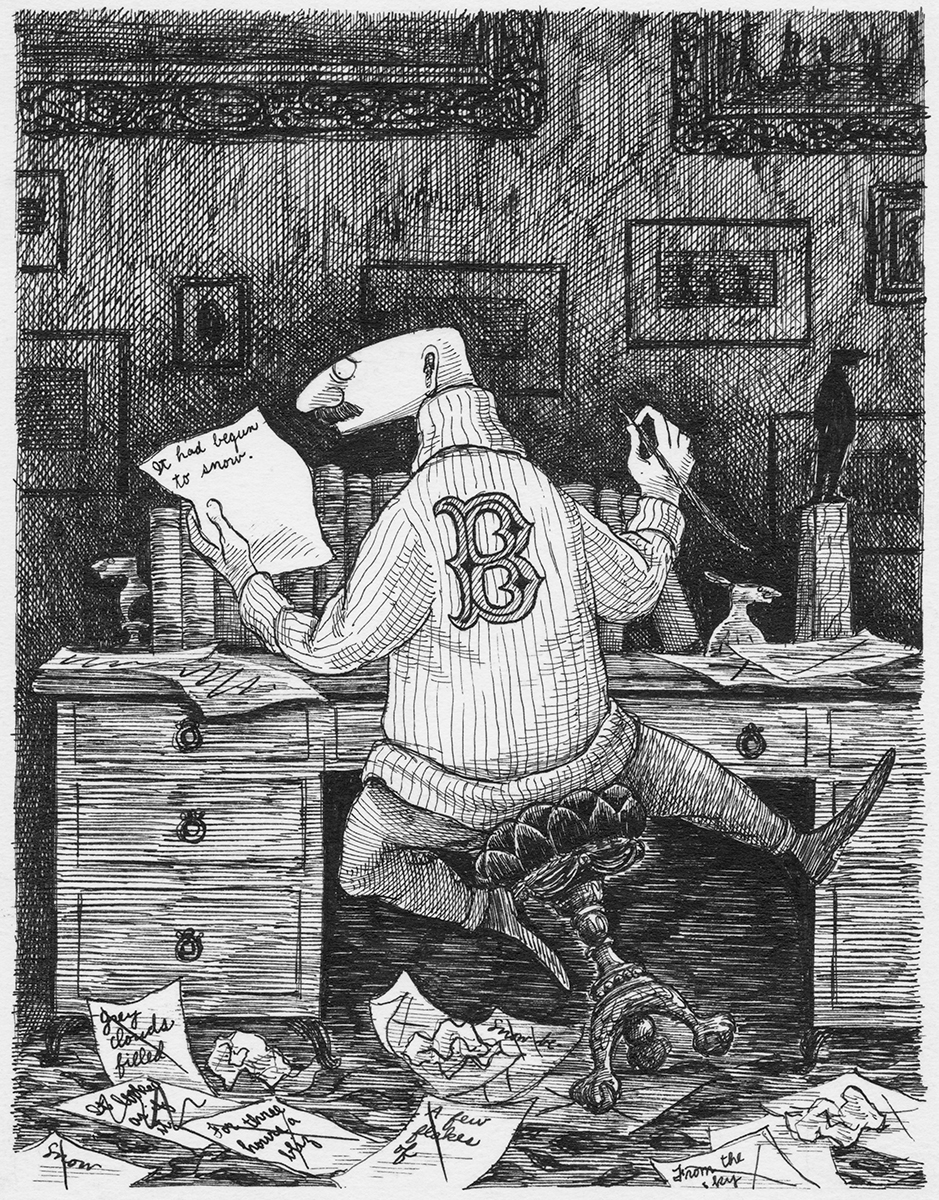

In his bulky athletic sweater, always worn hind-side-to. Mr. Earbrass inks up his pen to begin TUH (Gorey’s abbreviation throughout the book). He “belongs to the straying, rather than to the sedentary, type of author. He is never to be found at his desk unless actually writing down a sentence. Before this happens, he broods over it indefinitely while picking up and putting down again small, loose objects; walking diagonally across rooms; staring out windows; and so forth.” On one of his rare breaks from writing Mr. Earbrass drives “to Nether Millstone in search of forced greengages” and passing a bookstore he comes across The Meaning of the House, his second novel, in the store’s discount bin. Leafing through it, and adding to his dismay, he finds it is a presentation copy, inscribed “For Angus — will you ever forget the bloaters— ?” His memory reels. Bloaters? Angus? Back at Hobbies Odd, Mr. Earbrass, while skimming through the early chapters, rashly declares them dreadful! “He must be mad to go on enduring the unexquisite agony of writing when it all turns out drivel.” He will burn the manuscript, but there is no fire or the makings of one.

At last, recovered from his bout of doubt, “in that brief moment between day and night…Mr. Earbrass has written the last sentence of TUH.” Then with paste pot, pen, ink, scissors, and a decanter of sherry he begins revising the manuscript. Before he is through, “at least one third of TUH will bear no resemblance to its original state.”Having undergone the tedium of making a clean copy of the manuscript, he wraps it up, drops it off at the offices of his publisher, Scuffle & Dustcough, and before returning home, attends a private literary dinner with fellow authors. The talk is all about disappointing sales, inadequate royalties, inadequate publicity, and “the unspeakable horrors of the literary life.”

Before Mr. Earbrass realized it, galleys for TUH arrived. Approached “with mingled excitement

and disgust” he noticed it “all looks so different set up in type that at first he thought they had

sent him the wrong one by mistake.” Then came the sketch for the cover. What were they

thinking of? That drawing. Those colors. Ugh,” winces Mr. Earbrass. He spent an hour

conveying his sentiments to Scuffle and Dustcough. Finally, his free author copies were

delivered, but only six, not near enough to give to all who expected a copy. And buying more wasn’t the answer. He couldn’t satisfy everyone no matter what.

The day that TUH was published Mr. Earbrass was in Nether Millstone on some much-needed errands when he paused to look in a bookstore window. Out of the corner of is eye he saw a copy of TUH was in it, then he read “the title of every other book there in a state of extreme and pointless embarrassment.” Back in his favorite armchair, he attempts to press on in A Compendium of the Minor Heresies of the Twelfth Century in Asia Minor, while studiously ignoring the heap of print reviews forwarded to him by the publishers.

At an afternoon gathering, vaguely in his honor, Mr. Earbrass is “brought up short by Col. Knout, M.F.H. of the Blathering Hunt.” He demands to know just what the author was “getting at in the last scene of Chapter XIV.” Mr. Earbrass doesn’t know what the Colonel was getting at himself. The Colonel snorts. Mr. Earbrass sighs, and leaves “feeling very weak indeed.” Before he knew what he was doing, Mr. Earbrass made plans for a few weeks on the

Continent. He assumes he will be horribly sick over he churning Channel, but no matter. “Though he is a person to whom things do not happen, perhaps they may when he is on the other side.”

So ends Gorey’s prescient view into the life of a published author; prescient because TUH was written two years before he became a published book author himself! As a book cover artist, designer and art director for major publishers he could see the paces authors are put through, but it wasn’t until TUH that he was thoroughly immersed in the process to capture. To capture so utterly true—and with delectibly dry wit— the nuances of self-doubt, deadline pressures, tough competition, and dubious public acceptance, he must have experienced them as he was writing the book.

For example, when Mr. Earbrass confronted the printed galleys he was surprised how his words looked so different set up in type “that at first he thought they had sent him the wrong one by mistake” Gorey had a similar unexpected revelation as he recorded in a 1953 letter to Alison Lurie: “I was somewhat taken aback to discover that when it came time to read the galleys of The Unstrung Harp it all looked so final set up in type that I didn’t have any way of getting back into it, so I left them virtually alone; I had expected to want to rewrite practically everything in the worst way.”1

Every word in Gorey’s writing is carefully considered. An indication to how correct the writing for his first published book must be, may reside in his dedication to TUH that reads: “for “Whatever were they thinking of” R.D.P.” The initials stand for Richard Poirier an acquaintance who shared Gorey’s devotion to George Balanchine’s ballet performances as noted by Edmund Wilson in his article for the New York Times, “The Man Who Knew Ballentine”

“The lobby of the State Theater was the one place where you could see, night after night, literary intellectuals like Susan Sontag, the poetry critic David Kalstone, the essayist Richard Poirier, the cartoonist [!] Edward Gorey, the music and dance critic Dale Harris, the editor of Knopf, Robert Gottlieb — and dozens of others.”

Poirier was also a noted man of letters a graduate of both Yale and Harvard, co-founder and board chairman of the Library of America, Professor of American and English Literature at Rutgers University, and editor of Partisan review, among other scholarly pursuits. It is most likely that Gorey dedicated TUH to Poirier as a friendly gesture to a fellow book enthusiast, as opposed to a critic looking over his shoulder as he’s writing and to whom Gorey must answer just what was he getting at in his book.

When it comes to his creativity, Gorey answers to no one. His first book is pure magic, about which renowned novelist Graham Greene said: “… Edward Gorey’s The Unstrung Harp is the best novel ever written about a novelist, and I ought to know.”

1. ltr to Alison Bishop, “Saturday evening” Apr, 1953

2. nytimes.com/books/98/11/08/bookend/bookend